After

Foxy and Piggy were given the boot, Rudolf Ising changed

Merrie Melodies to a one-shot series, and It's

Got Me Again!

(1932) is a prime example of the series' new direction. While not an

extraordinary cartoon, it holds the distinction of being the first

Warner Brothers short to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best

Animated Short Film, 1931-1932 being the first year the Oscars

recognized such a category. It lost to Disney's Flowers

and Trees

(Disney would win the first 8 Oscars for animated shorts). It's Got

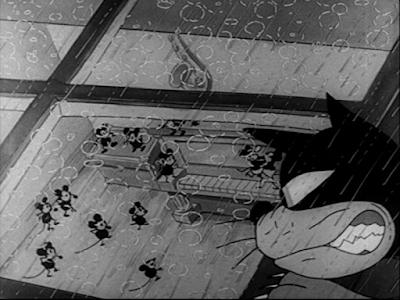

Me Again! follows a group of Mickey Mouse-caricatures singing and

dancing in a house as it pours down rain outside. As is typical of

the early Warner Bros cartoons, there is an over reliance on the same

generic happy-go-lucky music, performed by wide-smiled characters, or

who perform actions synced to these songs. Watching several

Harman/Ising shorts in succession can be a tedious affair because of

their reluctance to break formula, their cartoons

often aiming for one mood, and rarely diversifying. It's

Got Me Again!

has a couple passable minutes near the end, when an antagonistic cat

observes the mice from afar, and breaks into the house and chases

them. But because he's introduced too late, the mice scare him away

rather easily, deflating any menace he's supposed to present.

I

Love a Parade

(1932) is a plot-less Merrie Melodies of little interest. It simply

goes through the motions of showing a circus, cutting from one act to

another, after the audience-opening musical performance of the title

song. It's structured as a compilation of thirty second bits, as we

go from varying acts such as a strong man, a rubber man, a bearded

lady, clowns, and animals. Often time characters are positioned

centre frame staring at the camera. In animation, structure, gags, or

plotting, there's just nothing interesting here.

Ride

Him, Bosko

(1933) throws its hero in the wild west, with many of the expected

gunslingers shooting and stagecoach chasing one comes to expect in a

comedy western cartoon. There are several lengthy sequences that

don't even feature Bosko.

There are a couple worthwhile gags, such as a male piano player who

downs a glass of foamy beer, catches on fire, and transforms into a

woman, strutting off-camera. And another, when a stagecoach driver's

luggage suitcase falls off and lands on the ground, cracks open, and

every article of clothing – each one a living creature – stands

up and runs away. Moments later, the same driver – who is being

chased by robbers – is blown off his ride and lands on a pile of

bull bones, which then spring to life and ride off with the old man.

Ride Him, Bosko is most famous for its ending, which ends on a

deliberate anti-climax. Honey is still kidnapped, and Bosko chases

after the robbers to rescue her, and the camera pans out in

live-action to the animators – Hugh Harman, Rudolf Ising, Friz

Freleng – discussing how they'll write Bosko out of this mess. They

shrug off his troubles, grabs their coats, and decide to go home,

leaving Bosko's story on an indefinite hold. This is one of the first

instances of meta storytelling in a Looney Tunes film, although they

would learn to break the fourth wall in far more satisfying ways in

years to come. This scene partly feels like a cop-out, because as earlier

shorts have shown, Harman and Ising are not invested storytellers. In

this instance, they ran out of time for Bosko save the day. It feels like an ending they approached as a way to quickly end the

picture without removing any earlier scenes. Considering Harman and Ising's other cartoons, it's difficult to say for sure if Ride Him, Bosko's fourth-wall-breaking ending is a result of innovation or inertness.

Bosko in Person

(1933) is a carefree Looney Tune featuring Bosko and Honey performing a

vaudeville set to an approving audience. And that's it. Nothing goes

wrong, there are no distractions. A series of gags are performed without

a hitch. As can be expected, it is smoothly animated and well timed,

but there is little to remember. There is a little too much tap dancing

and singing and celebrity impersonation (from Greta Garbo to Jimmy

Durante), but there are a couple enjoyable moments, like when Bosko's

glove comes to life and leaves his arm, while the two pull off a

variation of a ventriloquist routine, or later in the film when Honey

performs a solo dance while a strobe-light effect flashes, inverting the

blacks and whites on-screen back and forth for several moments,

creating a freaky - and perhaps unintentionally disturbing - sequence.

Bosko in Person is a basic song-and-dance short that does little to alter formula.

Rudolf Ising's I Like Mountain Music (1933) may seem familiar at first-glance, a precursor to Bob Clampett's classic Book Revue

(1946), in the books-come-to-life genre of animated short. Instead of

the more common choice of classic literature (also seen in another

Warner Bros short from 1933, Three's A Crowd), it's magazines on a

magazine rack. There are cowboys who exit a western magazine and fire

guns, detectives who exit a crime mag and snoop for footprints, and

Edward G. Robinson is seen leaving a movie mag. And of course, it

wouldn't be a post-Piggy Merrie Melodies without a cast of characters

singing the song the short is named after.

Shuffle off to Buffalo

(1933), another Merrie Melodies, has an interesting setting: baby

heaven, as Jerry Beck describes it. And it sorta is. It's an

interpretation on the storks-delivering-babies story, with a daycare far

up in the clouds run by a bearded old man who prepares the children for

their eventual life on Earth before being sent away to a loving couple

via stork. There are some racist elements to this one, with Jewish and tribal stereotypes in an attempt to represent a diverse

selection of children. This short is naturally cutesy, but nauseatingly

so; schmaltzy takes on storks and babies and perfect hetero-normative

couples. The baby voices used throughout fall on the shrill side, and

there's a little bit of screeching, so when it does break out into song,

the musical performance is a welcome distraction.

We're in the Money (1933) is sorta like Toy Story

only without any comedy, emotion, story, it's only seven minutes, and

you'll easily forget ever having seen it. A night watchmen leaves a toy

store, and all the toys come to life and dance and sing along to "We're

in the Money", then-recently made famous by the Warner Bros film Gold Diggers of '33. This is generic even by Merrie Melodies' already low standards in 1933.

This time in inanimate-objects-gaining-sentience, silverware run amuck in The Dish Ran Away with the Spoon

(1933), before banding together to save their house from a monster made

of dough. That last part only occupies the last couple minutes, so most

of this is plates and spoons doing tasks like washing the dishes, which

is sorta like people taking showers, only in this society, it's more of

a communal experience. Romantic songs are sung while budding lovers

with ugly barely-visible faces reflected on their silverware bodies

dance. None of the gags in the early going are particularly funny, but

the dough-monster transformation is very well animated, and seeing it

attacked by things like cheese shredders and rolling pins makes for a

cleverly executed final act.

Bosko's Picture Show

(1933) puts its title character on the back-burner for most of its

duration, as Bosko programs a features of short films and news clips for

a movie house, none of which he appears in. The news reels are

painfully lame; for instance, a title card predicting good weather

followed by a video clip showing snow and rain instead. There's one

accurate gag that shows a diplomatic peace talk which is actually a

roomful or politicians hitting each other and screaming. There's a

pretty weird bit where Adolf Hitler chases actor Jimmy Durante with an

ax. Then, Bosko's Picture Show transitions into comedy shorts, if

uninspired caricatures of movie stars the Marx Brothers and Laurel and

Hardy is your idea of comedy. Even calling these gags parodies would be

a stretch, as there's nothing here being made fun of or commented on.

This short tries to get by on the recognition of its familiar faces

alone without having to supply jokes. Bosko inserts himself into the

action at the end when he jumps through the screen to rescue Honey (who

is trapped inside the film) from an old fashioned movie villain.

Hugh

Harman and Rudolf Ising routinely wanted higher budgets to produce

cartoons, butting heads with Leon Schlesinger, who refused to cut his

own profits to give the animators more money. Partway through 1933,

Harman and Ising cut ties with Warner Brothers, and took Bosko with

them. Harman and Ising had a prior career mishap when their lost the

rights to their character Oswald the Rabbit to Disney, so made sure in

creating Bosko they possessed ownership. They took Bosko to MGM, and

later revived the character over there (in a more blatantly racist

depiction than before). In the long-run, ridding themselves of Bosko was

a step forward for Warner Brothers Animation, but in late 1933 it put

them in a tight spot, with no Looney Tunes star, and no head animation

director. The young animators Friz Freleng and Bob Clampett were hired

by Harman-Ising and had worked for them. Additionally, Schlesinger hired

them in their absence to ensure they stuck around. Schlesinger brought

in talent from Disney to be the supervising animators/directors, Jack

King and Tom Palmer.

Looney Tunes debuted its second star character in September 1933, with Buddy's Day Out

(1933), directed by Tom Palmer. Buddy is a lot like Bosko, except he's a

white child with more obvious human features, and shockingly has even

less personality, probably making him the most bland leading man in the

history of animated shorts. He goes out with his girlfriend Cookie, and

his dubious baby brother Elmer and his dog Happy. Buddy and Cookie

attempt go for a drive, and a date, but the fiend from hell that is

Elmer causes ruckus after ruckus, putting a damper on the couples' day.

Bosko cartoons are often hampered by lazy comedy, but Buddy cartoons are

often devoid of humour entirely. Buddy often finds himself in

situations where comedy is often expected, and as a viewer we can see

where amusing situations are supposed to be utilized for gags, but Buddy's Day Out

makes no effort to put a smile on anybody's face. It's like a rough

outline of a cartoon where the writer inserted a lot of "[insert joke

here]" throughout but never went back to put in the jokes. It's also a

step below Bosko cartoons in the animation department. Under Tom

Palmer's supervision, Buddy's Day Out is much cruder and uglier

drawn than any Harman and Ising Warner Brothers short. Harman and

Ising's style could be basic, but it was competently attractive. Buddy's Day Out

is amateur in comparison, with its lumpy figures and unflattering

characters. Its backdrops are fine, but nothing happening in the

foreground is ever fun to look at.

I've Got to Sing a Torch Song

(1933) is Tom Palmer's second and last film with Warner Brothers. With

both this and Buddy's Day Out, his supervision was infamously loose, to a

point where he failed to create any gags in story meetings, and

expected the animators alone to carry the load. Warner rejected this

lazy approach and promptly fired him. Friz Freleng had to extensively

rework Palmer's shorts, and was soon after promoted to director (Earl

Duvall was the director immediately following Palmer and preceding

Freleng). I've Got to Sing a Torch Song is a formulaic Merrie

Melodies made up entirely of isolated gags from around the globe, of

various radio listeners responding variably to the title song being

broadcast. There's even a montage of racist caricatures in the midway

point, cutting from listeners who are Chinese, Eskimo, Arab, even

African cannibals. It's as if the film is trying to outdo its awfulness

with every succeeding scene. Palmer's shoddy supervision and subsequent

firing is probably a big reason why his two shorts are badly

animated. Without proper direction for the animators, and a reworking

period that couldn't have possibly allowed for entire scenes to be

redrawn from step one, the resulting animation is crude and unappealing;

the faces in I've Got to Sing a Torch Song are ghastly to look at, particularly the celebrity likenesses.

Earl Duvall replaced Tom Palmer, his first short being Buddy's Beer Garden

(1933). Duvall only lasted slightly longer than his predecessor,

cutting ties with Schlesinger after completing five shorts, departing in

1934. Of note about Buddy's Beer Garden is that it maybe

contains the first title card credit of young animator Frank Tashlin for

a Looney Tunes or Merrie Melodies cartoon, though he started working

for Warner earlier in the year with uncredited contributions. Buddy's Beer Garden

is an unremarkable and plot-less affair, with Buddy and Cookie running a

brewery and serving a rowdy group of German patrons, while live

entertainment is performed. Barely anything in this film could register

as humour; it's cutesy fluff that goes down easy.

Sittin' on a Backyard Fence

(1933) is an Earl Duvall Merrie Melodies about two male stray cats

fighting for the affection of a lady cat. In the end the two strays

discover their fighting was over nothing, as the woman already has a

partner, and a litter of kittens to boot. Like every Merrie Melodies of

the era, there are a lot of brief sequences with animals and/or

inanimate objects springing to life to sing a few lines of whatever song

is playing, but what's surprising about Sittin' on a Backyard Fence

is that it actually tells a story in-between these moments. It's a

simple narrative, but most of these tend to be plot-less, so it's a

welcome change. It's not a particularly memorable cartoon, but it does

have a visually interesting climax action scene atop telephone wires,

wherein the two cats are balancing on a rolling pin going across the

wires, while they still attempt to fight. The perspective changes

without any frame cutting, as it gives the illusion that the cats are

traveling across multiple blocks of telephone wires. The action swifts

from left to right or top to bottom, but always stays with the cats.

It's a reworking of the classic action climax used previously in Bosko

and Foxy films. In those, it was usually on a train and train tracks, or

an open road and a vehicle; here, it's been remodeled to take place up

high, as the camera points downward at the passing buildings below. It's

not a ground breaking piece of animation, and some of it does look

awkward, but it's one of the more formally interesting sequences the

Warner Brothers animators have attempted up to this point, and is a step

in the right direction.

1933

was a tumultuous transitional year for the Warner Bros animation

studio, but the key players are slowly coming together. Friz Freleng is

promoted to director following Duvall's departure. Frank Tashlin, Bob

Clampett, Robert McKimson and Chuck Jones are all working - mostly

uncredited - in the animation departments. And Schlesinger is close to

hiring the radical young genius who would help shape the Looney Tunes identity by pushing it away from its Disney copycat incarnation of the early '30s, in

Tex Avery.

Note: I will not be watching every single Looney Tunes and Merrie

Melodies film, only the ones made easily available across the essential

DVD and Blu-ray video compilations (Golden Collection, Looney Tunes

Super Stars, Chuck Jones Mouse Chronicles, Platinum Collection, Warner

Archive's Porky Pig 101)

Historical information in this and following installments come from three invaluable sources:

Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons, by Leonard Maltin

Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in its Golden Age, by Michael Barrier

Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies: A Complete Illustrated Guide to the Warner Bros. Cartoons, by Jerry Beck & Will Friedwald

Comments

Post a Comment