Island Adventures; Running through Godzilla Part 4: 1966-1967

As

if sensing the series was growing stale with Invasion of Astro-Monster, Toho hired a new director to helm the Godzilla series,

Jun Fukuda. 12 years Ishiro Honda's junior, Fukuda had been directing

modest sized comedy and mystery films since 1959, but nothing of note

to Western audiences. After making four Godzilla films in four years,

Honda's entries were growing less exciting. He would still have great

'Zilla films up his sleeve, but a little distance was necessary for

him to recharge. Fukuda gave the series a much needed change in

direction, his films brighter, friendlier, and a more guilt-free

version of family entertainment that Toho likely appreciated.

Fukuda

makes his presence known early in

Ebirah, Horror of the Deep

(1966), also known as Godzilla

vs The Sea Monster,

in a lengthy dance competition sequence. In a wide shot, dozens of

men and women are shown in brightly coloured shirts dancing their hearts out,

the winner of the endurance contest receiving a luxury boat. It's a

bright playful scene that would seem out of place in a Honda picture.

Fukuda embraces '60s youth culture, and fills the film with young

actors. The film's protagonists lose the competition, but steal a

yacht anyway and head out to sea, hoping to find the main character's

lost-as-sea brother. During a terrible storm, the yacht comes head to

head with a giant lobster monster, Ebirah, causing them to shipwreck

on an island. This is the first of two back-to-back island adventure

movies. This was simply a cost cutting measure by Toho. By moving

action away from the cities of Japan, they didn't need to hire as

many actors, or create as many miniatures or full-sized sets. It

helps to visually set these movies apart from the predecessors, the

movie utilizing both the barren plateaus and the rocky mountain

terrains compared to the mostly metropolitan affairs directed by Honda.

Elsewhere

on the island a terrorist organization known as Red Bamboo is

manufacturing experimental heavy water as well as chemicals that keep

the deadly Ebirah at bay. They're also forcing the Infant Island

natives into slave labour, while their idol Mothra remains in a deep

slumber. The Shobijin aide the shipwrecked friends in planning to

foil Red Bamboo's plans, in what plays out like an action movie long

before we ever see a kaiju battle. The film's first half is modestly

entertaining, carried by the charismatic young leads and the beauty of the new terrains previously foreign to Godzilla. The Red Bamboo

laboratories and hallways are even appealing, with a geometric

attractiveness of long intersecting pipes of bright red, blue and

yellow. Fukuda's fondness of primary colours give his movies an

appealing look, that often help carry them through slower or more

plot-obligatory scenes. Watching the heroes sneak through a series of

long empty rooms is only so interesting; throw in elaborate sets and

a fun colour palette and these moments are already more pleasing to

watch.

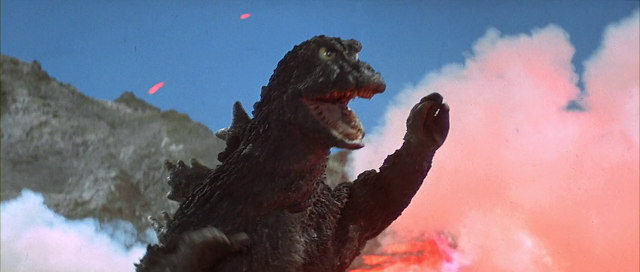

Godzilla

has been at rest inside one of the island's mountains, and is

awakened by a lightning rod, making his first appearance in Ebirah,

Horror of the Deep at

the 53 minute mark. The film then wastes no time pitting the two

monsters together, with Godzilla starring down Ebirah as he makes

several steps into the water. Without the collateral damage and

trauma felt by human life to worry about, Ebirah

focuses entirely on the kaiju, with the camera close behind their

backs as it cuts between the two, as they throw rocks, shoot beams,

and grapple one another above and under water. The camera even shakes

in its close ups, which adds a fly-on-the-wall intensity never quite

felt in Ishiro Honda's Godzilla movies. If there's one primary

difference between Honda's monster battles and Fukuda's monster

battles, Honda wants you to emphasize with the humans, whereas Fukuda

wants you to emphasize with the monsters. The monster suits continue

to improve, with the kaiju now having their best mobility in the

series to date, moving with the same nuance as human combatants.

Minutes later when Godzilla is attacked by a half dozen Red Bamboo

fighter jets, the film busts out a surf pop instrumental score. The

sight of 'Zilla swatting jets out of the sky like flies is

accompanied not by the sounds of screaming or of melodic doom, but of

music that wouldn't feel out of place on an early '60s Beach Boys

album. And the onlooking humans this time around aren't witnessing

the take down of fighter pilots with horror or disgust, but

satisfaction, because they and Godzilla happen to be working on the

same side.

A

fully grown Mothra flies in at the end to rescue all the people on

the island before its explosives go off, with our protagonists

looking back in dread, afraid of Godzilla's fate in the upcoming

explosion. They yell feverishly at him to get into the water, to swim

away from the island, even though they know he can't understand them.

When the smoke clears and they see the creature escaped just in time,

they scream in excitement. Godzilla caused no harm throughout the

film, and while working of his own volition was still against Ebirah

and the Red Bamboo. Ebirah,

Horror of the Deep furthers

Godzilla's evolution into a hero.

The hero becomes a father. Son

of Godzilla

(1967) is a radical departure in the franchise. While the second of

two island-themed movies back to back, and still directed by Jun

Fukuda, it sees another shift from Toho to push Godzilla even further

as family-friendly entertainment. This is one of the most

monster-centric movies in the series, which sets it apart from

Ebirah,

Horror of the Deep. Son of Godzilla takes

form with the arrival of a mysterious giant egg. Two

praying mantis kaiju, called Kamacuras, crack it open with their

pincers, probably in hopes of eating what's inside. The observing

humans – and audiences alike – are shocked at what hatches: an

infant humanoid lizard creature, which one of the humans immediately

describes as “a baby Godzilla!” We can predict where the film is

heading from here.

The

preying monsters jab at the newborn for a couple minutes, while the

confused baby tries to roll and crawl away. He opens his eyes for the

first time and sees the faces of his attackers, which cuts to an

extreme close up of their mouths. The scared child curls into a fetal

position and clamps his eyes shut, as the Kamacuras continue to poke

him. It's an upsetting sequence. There has been a growing empathy in

the monsters over the course of the series to now, which arguably

hits its sappy emotional peak in Son

of Godzilla.

Like Godzilla, the child is given large expressive eyes that

effectively communicate whenever he is scared or hurt. New to the

world, he lacks the experience and age of his giant creature peers.

He is helpless around enemies. He is also much too large for humans,

still; even child sized for a kaiju, he continues to mammoth over

people. This cements him as an outcast of sorts in this movie, as if

simply trying to guide his way through life in his earliest moments

wasn't struggling enough.

The baby Godzilla is named Minilla

in Godzilla canon, though it's not like Godzilla himself could have

given him this name, so it must have been attributed to him by

humans. He's pudgy, dumpy, and all around pretty ridiculous looking.

Scenes of him getting bullied by other monsters, or in conflict with

Godzilla, are sad to watch, because of how effectively his emotions

are being conveyed, but everything involving Minilla is also somewhat

hilarious because of how silly and unconvincing his rubber suit

looks. Godzilla's movements are also a little clunky in this film; he

isn't allowed the same grace he had in Ebirah.

It seems like the bulk of the creature budget was spent on the

villains. The Kamacuras have an anatomy unlike any we've seen in the

franchise so far, with four legs, a long upper body, two dangling

front limbs, and bulging yellow eyes. Their pincer arms are

constantly moving, their legs shifting in weight, as if they're

always planning an attack. Insect anatomy lends itself well to kaiju

design, and a large budget isn't necessary to make a creature look

scary, because many insects inherently already do.

After rescuing Minilla from the Kamacras, Godzilla reluctantly takes the child with him, and their scenes are more in touch with a family sitcom than a common monster movie. Godzilla fathers Minilla for a significant portion of the film, and it's interesting to see so many lengthy sections of Son of Godzilla using silent film techniques. Usually, the humans drive the narrative throughout the film, with the kaiju sequences delegated for action, but the humans became an afterthought with the hatching of the egg. Godzilla and Minilla's father/son relationship is this film's core component, which gives the battle scenes much higher stakes later. The father/son bonding is definitely a little cheesy, but it doesn't feel out of place in this movie's universe. Toho had been softening Godzilla's image increasingly with every movie in the 1960s up to '66, so seeing him raise an adopted monster baby elicits more of a “sure, why not” reaction than one of shock or betrayal. Midway through the film there's a couple-minute long scene of Minilla trying to entertain himself while Godzilla sleeps. He tries kicking a rock back and forth, until he trips up on it. He observes his surroundings, and notices 'Zilla's tail flicking back and forth, which Minilla sees as a game of jump rope. He jumps above the tail in between rotations until he falls yet again. Godzilla briefly wakes up, disgruntled, before dozing off again. Minilla walks around and the scene ends. There are several scenes of this nature, which are conflict free and interesting because they don't propel much of a narrative outside of Godzilla and Minilla attempting to form a relationship. These moments are refreshing to watch, and set Son of Godzilla apart from every other film in the franchise in a big way through their slapstick comedy and sincerity between reluctant father and eager son. This is perhaps the largest departure in the Godzilla franchise because of this relationship. In previous films the kaiji were given personalities, but the end goal was always the fight, and that does come into play here with Papa Zilla eventually showing Manilla how to shoot fire from his mouth, but it is in the digressions with Godzilla and Manilla that this film finds its heart.

After rescuing Minilla from the Kamacras, Godzilla reluctantly takes the child with him, and their scenes are more in touch with a family sitcom than a common monster movie. Godzilla fathers Minilla for a significant portion of the film, and it's interesting to see so many lengthy sections of Son of Godzilla using silent film techniques. Usually, the humans drive the narrative throughout the film, with the kaiju sequences delegated for action, but the humans became an afterthought with the hatching of the egg. Godzilla and Minilla's father/son relationship is this film's core component, which gives the battle scenes much higher stakes later. The father/son bonding is definitely a little cheesy, but it doesn't feel out of place in this movie's universe. Toho had been softening Godzilla's image increasingly with every movie in the 1960s up to '66, so seeing him raise an adopted monster baby elicits more of a “sure, why not” reaction than one of shock or betrayal. Midway through the film there's a couple-minute long scene of Minilla trying to entertain himself while Godzilla sleeps. He tries kicking a rock back and forth, until he trips up on it. He observes his surroundings, and notices 'Zilla's tail flicking back and forth, which Minilla sees as a game of jump rope. He jumps above the tail in between rotations until he falls yet again. Godzilla briefly wakes up, disgruntled, before dozing off again. Minilla walks around and the scene ends. There are several scenes of this nature, which are conflict free and interesting because they don't propel much of a narrative outside of Godzilla and Minilla attempting to form a relationship. These moments are refreshing to watch, and set Son of Godzilla apart from every other film in the franchise in a big way through their slapstick comedy and sincerity between reluctant father and eager son. This is perhaps the largest departure in the Godzilla franchise because of this relationship. In previous films the kaiji were given personalities, but the end goal was always the fight, and that does come into play here with Papa Zilla eventually showing Manilla how to shoot fire from his mouth, but it is in the digressions with Godzilla and Manilla that this film finds its heart.

But this is a kaiji film and there would have to be a fight. The Kamacuras are just a smokescreen and are wiped out late in the film with the arrival of the new big bad monster, a gigantic spider named Kumonga. It destroys the praying mantis' with ease, which immediately tells us how powerful this creature is, considering how much Godzilla struggled against the Kamacuras. Kumonga is one of the finest displays of puppetry in the early Godzilla movies, with a menacing character design that arachnophobes will find horrifying. The spider has been living under the earth, and is grotesquely brought to life, with a grimy rustic appearance. It has multiple visible textures; flesh, fur, bone. It moves with precise articulation. Its limbs move fluidly in many different joints. It looks absolutely enormous. The scaling in Godzilla movies can sometimes be a little iffy with regards to its monsters, and not as believable as desired, but Kumonga appears to dwarf even Godzilla himself, even though it's not necessarily the larger creature. The camera frequently places itself directly behind Kumonga, or towering over or under, so that it overpowers the foreground image; lingering on the monster's anatomy. Opposing kaiju are placed in the background, and are placed further away than the character would usually stand in a kauju battle, to create the illusion of significant size difference, to push forward the idea that even Godzilla could be outmatched by this enemy. It's smart blocking, that makes Kumonga the dominant figure in every frame.

Godzilla and Minilla are successful in defeating

Kumonga only after it is slowed down by the snowstorm activated by

the human scientists as a means of confining the monsters to the

island. Snow comes down hard in the film's final minutes, christening

the cinema screen in a hazy white glaze. The temperature plummets

further, a blizzard becoming an ice age. Godzilla and Minilla brave

the falling snow as they try to walk to shelter, but the child cannot

keep up, too cold to continue moving, and falls down in the snow. He

screams out to Godzilla, who hasn't noticed that he has fallen. He

tries to run back to Minilla, whose own movement now is growing slow

and weak. They embrace in a hug, with Minilla looking up to father,

concerned. 'Zilla holds on tight to his son, as they both soon freeze

in place. What could come across as a contrived or manipulative

finale is effective in its emotional notes. Through the father and

son bonding which ran solid throughout the film's last hour, we are

told a simple narrative of reluctant fatherhood. When Godzilla hugs

his son to protect him from an icy death, Son

of Godzilla

has earned that moment.

Godzilla and Minilla aren't really dead, we are told. The scientists make sure to tell themselves – and the audience – that the deep cold will merely put them into a hibernation. When the snow melts at the end of a season, they will awaken. This added dialogue cements Son of Godzilla as a family movie just as much as anything else that happens in it, ensuring there's a feel-good ending for its audience. It doesn't entirely devalue the end of the two hugging in the blizzard as they have no way of knowing it's only a hibernation sleep. The cries that Godzilla ring out indicate very well that he is knowingly approaching death. It's still a hard hitting finish, to what is one of the most fascinating and entertaining of all the Godzilla films.

Godzilla and Minilla aren't really dead, we are told. The scientists make sure to tell themselves – and the audience – that the deep cold will merely put them into a hibernation. When the snow melts at the end of a season, they will awaken. This added dialogue cements Son of Godzilla as a family movie just as much as anything else that happens in it, ensuring there's a feel-good ending for its audience. It doesn't entirely devalue the end of the two hugging in the blizzard as they have no way of knowing it's only a hibernation sleep. The cries that Godzilla ring out indicate very well that he is knowingly approaching death. It's still a hard hitting finish, to what is one of the most fascinating and entertaining of all the Godzilla films.

Comments

Post a Comment