All-Out Kaiju Battle Royal in Destroy All Monsters (1968)

"The 20th century is nearing its end." Destroy All Monsters' opening line said via narrator, as they go on to explain the technological and militarist advancements made by Japan since the modern era. Every previous Godzilla film occurs in the then-present, so we have to assume this is a version of Japan 30 years after dealing with the regularly occurring ecological disasters of Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964) and Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964). The film's opening 30-second dolly shot pans over the sophisticated United Nations Science Committee (UNSC) base constructed from miniatures; a base busy with activity, the bustling of cars, helicopters taking off, even a futuristic rocket ship seconds away from blasting into orbit. The rocket's destination: Monsterland, Japan's latest pacifist-ish solution to their giant monster problem. Monsterland is an island with no near-by bodies of land, described by the film's scientist characters as a "research habitat of giant fearful monsters". In an amusing sequence, we see the Godzilla franchise's most casual on-screen kaiju introductions. "Godzilla is here", a narrator helpfully informs us right as Godzilla is seen walking out of a cave, seemingly yawning and stretching. Debuting in the film at the 3 and a half minute mark, this is a significant departure from earlier films waiting 30 or 40 minutes to introduce its title character. The kaiju roll-out continues, with shots of Rodan [a goofy looking pterosaur, debuted in Rodan (1956)], Anguirus [an ankylosaurus mixed with a crocodile, debuted in Godzilla Raids Again (1955)], Mothra (giant moth goddess who was killed in a previous film, name now carries over to larva offspring, debuted in Mothra (1961)], Gorosaurus (regular looking giant dinosaur, debuted in Toho's King Kong Escapes (1967)], and Minilla (clumsy child kaiju with resemblance to Godzilla, who acts as a father to the child, debuted in Son of Godzilla (1967)]. The island's magic-science is briefly explained, being that there are psychic and magnetic barriers which mentally and physically prevent the monsters from ever leaving Monsterland, or even venturing more than a few meters into the sea. The narrator informs us that the facility also acts as an underwater farm, constantly cultivating a large supply of animal life for the carnivorous creatures, with the island itself being ripe with enough vegetation for the herbivores. The kaiju are prisoners and the island their quarantine, but with Japan's sophisticated science, it is worth noting they're keeping Monsterland stocked with food, implying that they could have chosen to simply let the kaiju all starve to death or eat each other. The continued existence of these creatures is important; maybe to try and better understand them, and to give them their own place on the Earth, eliminating the possibility of them harming other civilization; they have chosen not to deprive them of life. There's no easy answer for what exactly to do with hundred-meter-long monsters walking the planet, beings which are simply too large to exist within the rest of the world, and the government's approach in Destroy All Monsters is one of the more thoughtful kaiju responses in any of these movies, flaws of imprisonment notwithstanding.

Deep underground we see the interior of the research facility, with dozens of uniformed scientists conducting business. A different kaiju is seen on every TV monitor; every creature is being monitored 24/7 (one must feel a little pity to the person on Minilla duty, whose life is a constant series of embarrassing pratfalls). When a mysterious cloud of fog forms throughout Monsterland, all communication, monitoring and quarantine devices are shut down, causing a panic and immediate investigation by the UNSC. Before the world has time to react, the monsters escape. Rodan attacks Moscow, creating wind gusts which pierce through buildings. Gorosaurus attacks Paris, digging up through the earth, causing historic monuments to collapse. Mothra is in Beijing, Manda [sea dragon, debuted in Atragon (1963)] in London, and Godzilla is in New York City. Godzilla lays waste to shore-side blocks with raging breaths of fire. No musical score accompanies this destruction, the sounds of emergency sirens and fire drown out every other noise in the world. News broadcasters around the globe suffering grief and shock in real time while being forced to describe the ongoing horrors. "The world's treasure is about to be destroyed by the monster." After several light-hearted movies from director Jun Fukuda which relocated all monster action to deserted islands, and an Ishiro Honda directed family installment that places its major battles in outer space, Destroy All Monsters sees a return to the Godzilla of motivated urban destruction. Cities are not the collateral damage of monster melee, they are the target. It's a scene that may have shocked some original audiences, acting against Godzilla's gradual face-turn throughout 1964-1967, with Honda reminding people what these movies used to be about. Destroy All Monsters is a have-its-cake-and-eat-it-too sort of movie, as it places its eventual climax in uninhabited terrain without a building or civilian in sight, but these earlier city attack sequences are fantastic, with some of the finest effects work the series has done in the 1960s. The miniature sets are large and gorgeous, and the explosions and fires feel mammoth.

Eiji Tsuburaya was a brilliant special effects artist who first made a name for himself creating miniature set-pieces depicting real-life battles in propaganda and other World War II based films. Tsuburaya worked on war dramas with Ishiro Honda, The Eagle of the Pacific (1953) and Farewell Rabaul (1954), depicting flight battles and crafting explosions. His collaborations with Honda continued with Godzilla (1954), which brought special effects heavy movies into Japan, creating the tokusatsu genre (the kaiju movie being a sub-genre under tokusatsu), a term which roughly means "special effects filmmaking". A decades-long fan of King Kong (1933) and Willis O'Brien's groundbreaking stop motion animation, Tsuburaya longed to make a movie like that for Japan. The budget and time constraints he was under prevented him from utilizing stop-motion, so out of limitation, suitmation was born. Through a combination of actors wearing monster suits, miniature sets, and matte compositing, Tsuburaya invented a budget and time saving method for creating giant monster movies. He worked closely with Toho and Honda thereafter, and was part of every Godzilla movie and many other kaiju movies up through Destroy All Monsters. When his workload grew so large, he formed Tsubyraya Productions, which oversaw more work than he could ever handle on his own. In tokusatsu productions, the special effects director is often given the utmost control over special effects sequences, while the director handles everything else, thusly to ensure a kaiju production's success, obviously the special effects director is of equal importance to the director. As the Godzilla series grew in popularity over the early to mid 1960s, it became apparent families and children were turning up to watch them, more and more. Tsuburaya found a calling, and wanted to entertain children above all else. Honda was against this gradual transformation, but Toho sided with Tsuburaya. When Honda quit the Godzila series after Astro-Monster, the movies remained in light hearted family territory for two more movies, under director Jun Fukuda. It's likely a combination of factors that led to Toho allowing Destroy All Monsters to have scenes of darker material following three kid's movies. Happy to have Honda return to give Godzilla a proper send-off, they allowed him to dictate more control over the entire picture (he is credited co-writer, as he was on the original film). Tsuburaya was less hands-on in the final years of his life (he died in 1970), assuming a supervising role instead of proper effects directing. He was also increasingly occupied with TV in the late 1960s, developing and showrunning the hugely popular Ultraman series. Tsuburaya's career in tokusatsu is bookended with the births of the two most iconic franchise's in the history of the genre, dominating cinema and television. Destroy All Monsters is the final Godzilla movie Eiji Tsuburaya worked on.

The reporter's play-by-play enthusiastically announces each kaiju's appearance towards the battle field, and the fact that they all show up one slightly after another is all the more theatrical; each monster gets its own entrance. The commentator doesn't shy away from nicknames either, hyping up Godzilla as "the king of monsters" as he walks into frame. Anguirus is announced as "Anguirus from the Asagri Plateau"; considerate of the announcer to give a hometown billing. Destroy All Monsters couldn't be more wrestling if it tried. Godzilla. Minilla. Mothra. Rodan. Anguirus. Manda. Gorosaurus. Baragon [subterranean reptile, debuted in Frankenstein vs. Baragon (1965)]. Kumonga [giant spider, debuted in Son of Godzilla (1967)]. All monsters have entered the battle field.

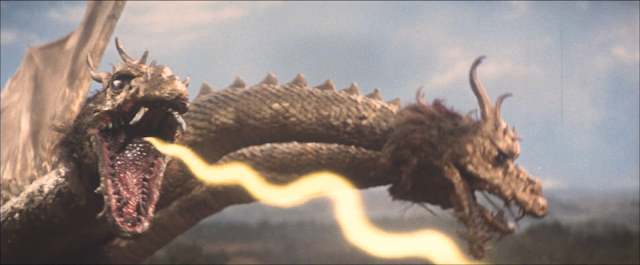

King Ghidorah has always dwarfed over the other monsters, but Destroy All Monsters showcases his size so well when compared to ten other kaiju, from a larva Mothra, to baby Minilla, to who's basically a smaller-less-efficient Godzilla in Gorosaurus. There is such a diverse sense of scale that it can be easy to forget there are people inside these costumes. To have so many costumed performers in one stage choreographing multi-pronged fights captures a sense of awe. Some monsters are more complicated, too, particularly the three heads of Ghidorah and the eight legs of Kumonga, which required on-set help to manuever in real-time. Ghidorah is eventually thwarted by the combined efforts of the Earth kaiju, and it's exciting and strangely cathartic to see the three-headed jerk get pummelled and humiliated so badly (Godzilla even calls over his boy Minilla to get a shot in, as Ghidorah lays limp on the ground). Some kaiju get more to do than others in this movie, however, with one of the oddest moments coming from a one-second cameo from Varan [giant flying squirrel monster, debuted in Varan (1958)], as if to steal a bit of the spotlight for having done literally nothing in the fight against Ghidorah. To connect this to wrestling again, Varan is the coward heel who hides underneath the ring during the entirety of the Royal Rumble only to crawl out and slide back into the ring at the very end.

Destroy All Monsters's all-out approach proved beneficial to Toho, with the film earning a warm reception, and a slightly higher box office gross than the preceding Son of Godzilla, temporarily pausing the series' downward trajectory. The King of the Monsters was far from dead after all, and Toho would actively churn out a nearly annual installment until the mid 1970s. At least commercially, those would be the dark days of Godzilla, with Destroy All Monsters being seen as one of the final triumphs of the Showa era. It certainly placed a precedent for every giant-monster all-out-attack movie to follow, and still casts a shadow over monster movies to this day.

-----

Historical information lifted from Godzilla FAQ, written by Brian Solomon, published by Applause: Theatre & Cinema Books

As of this writing, Destroy All Monsters is available for streaming on The Criterion Channel along with these other Showa-era Godzilla movies: Godzilla (1954), Godzilla Raids Again (1955), Godzilla: King of the Monsters (1956, US dub of the original), Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964), Ghidorah the Three-Headed Monster (1964), Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965), Son of Godzilla (1967), All Monsters Attack (1969), Godzilla vs. Megalon (1973), Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974), Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975), and Rodan (1956)

In 2016 as I watched through many Godzilla films (most for my first time), I chronicled my viewings of the first eight, spread across four posts.

Godzilla (1954) and Godzilla Raids Again (1955)

King Kong vs Godzilla (1962) and Mothra vs Godzilla (1964)

Ghidorah the Three-Headed Monster (1964) and Invasion of Astro Monster (1965)

Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1966) and Son of Godzilla (1967)

I likely will not be re-writing these earlier essays/reviews anytime soon and hope to continue moving forward. I believe stepping back for a few years proved beneficial, as I think I can approach kaiju movies more thoughtfully today than I did three years ago. These earlier pieces will remain up and are a decent-enough introduction to the early Godzilla movies.

Comments

Post a Comment